The design and construction of the Sophian Plaza is part of a larger story about the rise of the luxury apartment building at the beginning of the 20th century. The popularity of the new form of residence was developed in fever pitch in New York City, as Harry Sophian started his career. In the eight years, 1902-1910, some 4,000 apartment buildings were built.

At the end of the prior century, late 1800’s, the moneyed class considered apartment living to be the province of the poor, in the squalid tenements, derisively referred to by how many flights a resident had to climb, e.g., “fourth-floor walk-up.”

Yet, architects, engineers, and builders perfected designs, building materials, and elevators that could produce high rises, where residents floated up to their homes on upper floors. Tall buildings with elevators became a marketable feature, not an indicator of poverty. People enjoyed the relief from climbing stairs; they liked living suspended above the street chaos.

It was one thing to build a tall building, it required another impetus to make it a luxury building that would satisfy the status and amenity requirements of the wealthy. The developers adopted many features and services as enticements. First, architects adopted the Beaux Arts style (pronounced bowz-zar) that adapted the style of palazzos and grandiose public buildings of Europe. The style emerged from the premier French school of architecture, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and it draws on architectural forms of monumental Classicism, Italian Renaissance, and French Renaissance. Examples of the grand style were shown at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, to great fanfare. Beaux Arts (fine arts in English) synced with the City Beautiful Movement which inspired grand naturalistic, but composed parks.

Additionally, the new luxe apartment buildings offered the newest technologies and conveniences (electricity, central heat and cooling, telephones) far more affordably than retrofitting mansions of old. The stand-alone mansion had become an albatross, costly to operate, and downright primitive, compared with the modern paradise of new extravagant high rises.

Some commentators highlight that luxury buildings solved another upper-class problem: high turnover of servants. [Perhaps it’s no surprise that the moneyed class would consider their servants the problem, not their own behavior.] The apartment-building landlords provided door attendants, valets, elevator operators, grounds people, and the like.

Apartment “hotels” included the conveniences of restaurants that obviated preparing all meals, allowing families to have much smaller household staff. Individual apartment layouts provided service entrances for deliveries, tradespeople, and housekeepers, that were separate and distinct from the more gracious entrance for family and social guests. Many floor plans also included small bedroom(s) off the kitchen for live-in help. The new luxury apartment building allowed the affluent to live better than ever.

In NYC, apartment houses became the living style of choice

In New York City, the development of the luxury apartment hotel was energetic, creative, and experimental. By 1929 almost all upper- and middle-class residents in Manhattan were living in apartments, according to the historians describing works in the Irma and Paul Milstein Division of Local History at the New York Public Library,

“New York City’s housing law “not only legitimized the modern luxury apartment building, it bestowed a very specific blessing.””

The 1901 zoning law (called the Tenement House Law) authorized builders to erect fireproof buildings as tall as twice the width of the street. Effectively that meant 10-story tall buildings on the crosstown streets and 12-story buildings on the broad north-south avenues, with corresponding minimum building widths.

The greater building sizes allowed more creative apartment configurations. The impact of the new law has been chronicled by Elizabeth Hawes in New York, New York: How the Apartment House Transformed Life in the City (1869-1930). According to Hawes, the new law “not only legitimized the modern luxury apartment building, it bestowed a very specific blessing.” Of the 4,000 apartment houses were erected in Manhattan in those early years of the 20th century, many hundreds of them were designed for upper and upper middle classes. Hawes described the impact on New York City, “Of all the buildings that were erected in the first two decades of the millennium, none transformed the city more dramatically and more definitively than the new luxury apartment houses. … [T]he luxury apartment house was one of the great products of the American Renaissance. The millionaire had propelled the Age of Elegance into flowering and it was this gilded taste that now shaped a new generation of apartment houses.””

Harry’s birds eye view of nyc apartment development

This is the apartment building fever that Harry Sophian brought to Kansas City.

In New York, like elsewhere, Jews were unwelcomed in the mansion-filled, blue-blood neighborhoods of Fifth Avenue and the Upper East Side, flanking Manhattan’s Central Park. Instead, Jews established their own enclave on the west side of the Park, the neighborhoods called the Upper West Side and Morningside Heights. That was Harry Sophian’s working territory. The luxury apartment building blossomed in those neighborhoods. Immigrant architects (both Italian and Jewish) designed extravagant buildings that became home to the extraordinarily wealthy as well as the merely affluent.

There are a few architects and buildings that Harry might have found inspiration. Emery Roth, a Jewish architect of renown, designed many apartment buildings on the Upper West Side. His reputation bloomed after he designed the famous Chocolate Pavilion at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, the showcase event for the Beaux Art movement. Notice the colonnade, Corinthian columns, balustrade, and free-standing statuary of the pavilion. Each are central features of Beaux Art design, and each was incorporated into the Sophian Plaza design.

1893 Columbian Exposition

Showcase for beaux arts architectural design

Chocolate Pavilion, architect Emery Roth

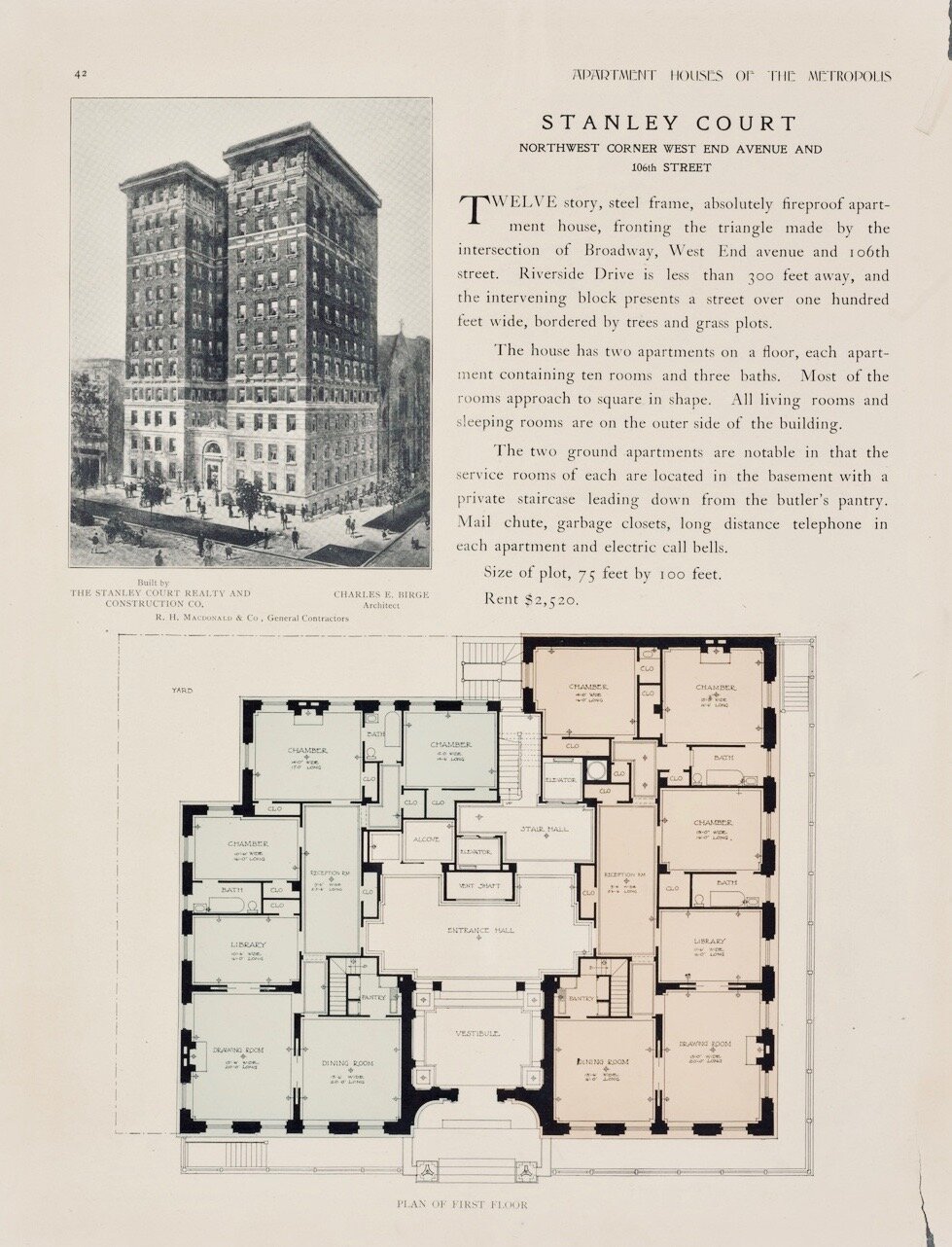

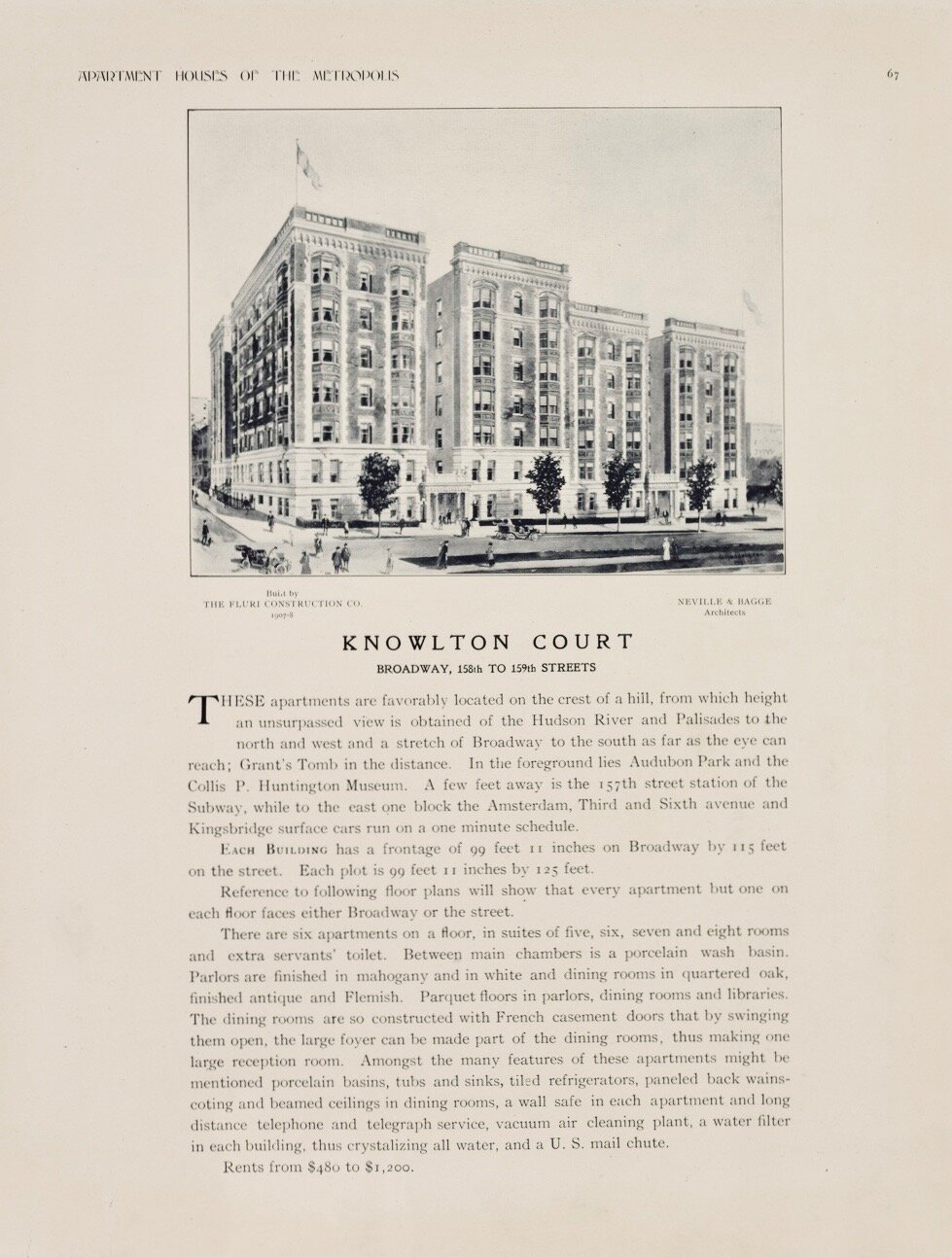

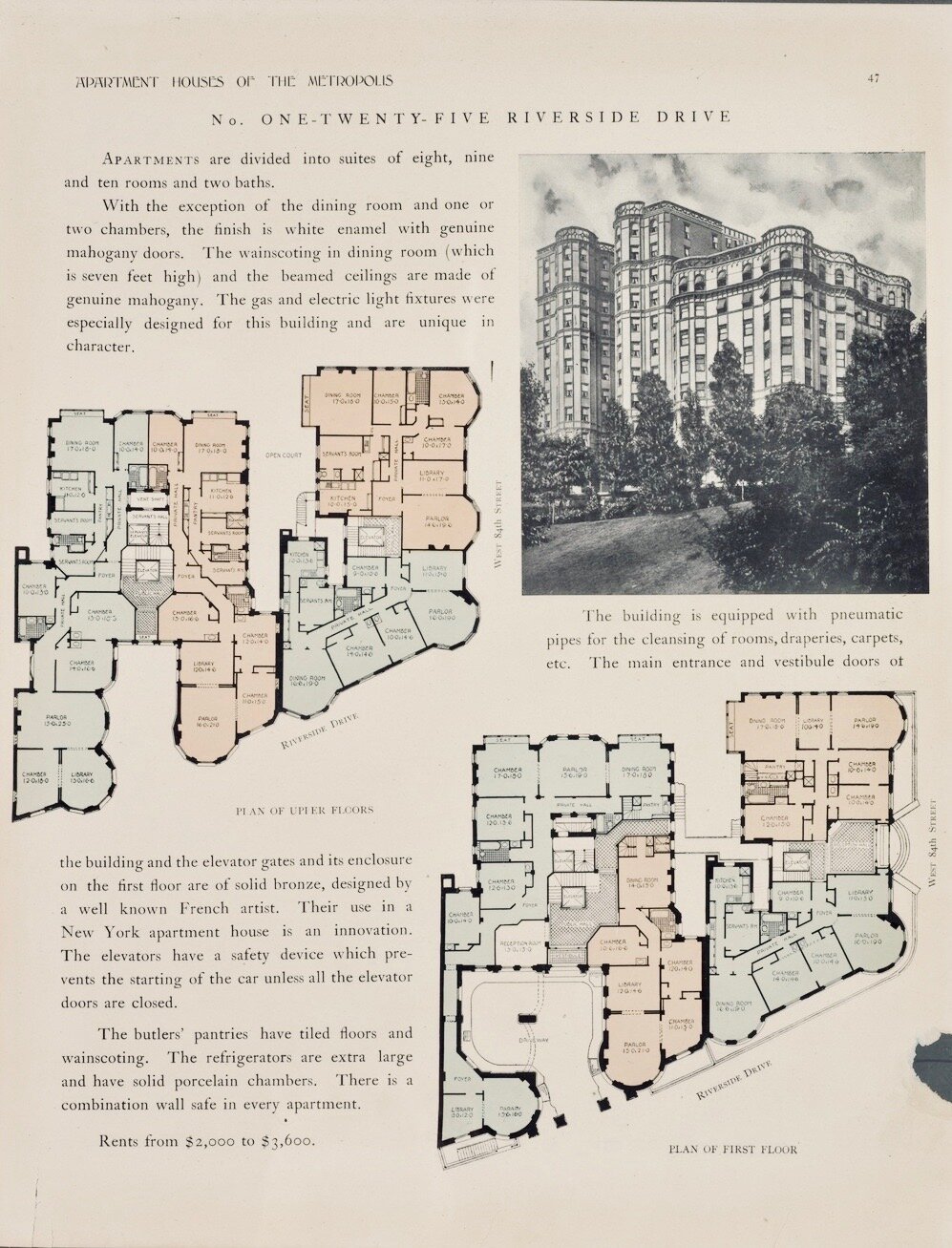

The Upper West Side apartment houses were grand, heavily ornamented, and designed in various architectural styles, most notably Beaux-Arts. These new buildings offered apartments of nine to twelve rooms. The chambers were large, with high ceilings and lavish interior details, including well-appointed bathrooms and kitchens, and ample closets.

A promotional book featuring select apartment buildings was produced annually, Apartment Houses of the Metropolis. They were created to entice potential middle- and upper-class tenants to New York City’s “principal high-class apartment houses.” It provides a glimpse into the exuberance of apartment house building on the Upper West Side. These 300-page volumes showed exterior shots of the featured buildings with description and often one or more floor plans. They were published annually from 1908 to 1913. The excerpts below are from the 1908 edition.

From these few examples, one can see parallels to the Sophian Plaza design. Limestone clad lower floors, topped with brick upper floors. Commonly, the building’s footprint was crafted to allow multiple facades for windows and air circulation.

Two of Harry’s siblings lived in buildings that were featured in these promotional books, Abraham and Rosie.

The Orienta

302 West 79th street

Abraham and Estelle Sophian’s residence, 1915 (per his passport application)

The st regis

830 East 163rd Street, Bronx

Rosie [Sophian] and Morris Rabinowitz residence, 1910 (per the Census)

Parallel Residential Forces in Kansas City

Kansas City historians have traced the development of apartment buildings here, noting that a segment of the upper-middle class emerged as an important subpopulation of apartment dwellers in the late 1880s forward. As the old elite neighborhoods close to the business centers declined, “apartment hotels offered amenities typically provided by hotels located on major thoroughfares with streetcar lines near the City's business centers. These new residential buildings featured an array of facilities and services for those without the time or inclination to manage a large home - kitchen, laundry, and maid services; well-appointed public rooms; and private suites that included parlors, dining rooms. bedrooms, bathrooms, and maid quarters. Social registers from the first decades of the twentieth century reveal that these apartments appealed to the upper-middle classes, including professionals, businessmen, and entrepreneurs.” Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Sept. 20, 2007).

The Sophian Plaza was conceived and designed to fit this role.