The Sophian through the Seasons- A Photo Journey

Photography courtesy of David Vranicar.

Winter holiday glow.

Winter wonderland.

Sunny days, blue skies.

Blog

The design and construction of the Sophian Plaza is part of a larger story about the rise of the luxury apartment building at the beginning of the 20th century. The popularity of the new form of residence was developed in fever pitch in New York City, as Harry Sophian started his career. In the eight years, 1902-1910, some 4,000 apartment buildings were built.

At the end of the prior century, late 1800’s, the moneyed class considered apartment living to be the province of the poor, in the squalid tenements, derisively referred to by how many flights a resident had to climb, e.g., “fourth-floor walk-up.”

Yet, architects, engineers, and builders perfected designs, building materials, and elevators that could produce high rises, where residents floated up to their homes on upper floors. Tall buildings with elevators became a marketable feature, not an indicator of poverty. People enjoyed the relief from climbing stairs; they liked living suspended above the street chaos.

It was one thing to build a tall building, it required another impetus to make it a luxury building that would satisfy the status and amenity requirements of the wealthy. The developers adopted many features and services as enticements. First, architects adopted the Beaux Arts style (pronounced bowz-zar) that adapted the style of palazzos and grandiose public buildings of Europe. The style emerged from the premier French school of architecture, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and it draws on architectural forms of monumental Classicism, Italian Renaissance, and French Renaissance. Examples of the grand style were shown at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, to great fanfare. Beaux Arts (fine arts in English) synced with the City Beautiful Movement which inspired grand naturalistic, but composed parks.

Additionally, the new luxe apartment buildings offered the newest technologies and conveniences (electricity, central heat and cooling, telephones) far more affordably than retrofitting mansions of old. The stand-alone mansion had become an albatross, costly to operate, and downright primitive, compared with the modern paradise of new extravagant high rises.

Some commentators highlight that luxury buildings solved another upper-class problem: high turnover of servants. [Perhaps it’s no surprise that the moneyed class would consider their servants the problem, not their own behavior.] The apartment-building landlords provided door attendants, valets, elevator operators, grounds people, and the like.

Apartment “hotels” included the conveniences of restaurants that obviated preparing all meals, allowing families to have much smaller household staff. Individual apartment layouts provided service entrances for deliveries, tradespeople, and housekeepers, that were separate and distinct from the more gracious entrance for family and social guests. Many floor plans also included small bedroom(s) off the kitchen for live-in help. The new luxury apartment building allowed the affluent to live better than ever.

In New York City, the development of the luxury apartment hotel was energetic, creative, and experimental. By 1929 almost all upper- and middle-class residents in Manhattan were living in apartments, according to the historians describing works in the Irma and Paul Milstein Division of Local History at the New York Public Library,

“New York City’s housing law “not only legitimized the modern luxury apartment building, it bestowed a very specific blessing.””

The 1901 zoning law (called the Tenement House Law) authorized builders to erect fireproof buildings as tall as twice the width of the street. Effectively that meant 10-story tall buildings on the crosstown streets and 12-story buildings on the broad north-south avenues, with corresponding minimum building widths.

The greater building sizes allowed more creative apartment configurations. The impact of the new law has been chronicled by Elizabeth Hawes in New York, New York: How the Apartment House Transformed Life in the City (1869-1930). According to Hawes, the new law “not only legitimized the modern luxury apartment building, it bestowed a very specific blessing.” Of the 4,000 apartment houses were erected in Manhattan in those early years of the 20th century, many hundreds of them were designed for upper and upper middle classes. Hawes described the impact on New York City, “Of all the buildings that were erected in the first two decades of the millennium, none transformed the city more dramatically and more definitively than the new luxury apartment houses. … [T]he luxury apartment house was one of the great products of the American Renaissance. The millionaire had propelled the Age of Elegance into flowering and it was this gilded taste that now shaped a new generation of apartment houses.””

This is the apartment building fever that Harry Sophian brought to Kansas City.

In New York, like elsewhere, Jews were unwelcomed in the mansion-filled, blue-blood neighborhoods of Fifth Avenue and the Upper East Side, flanking Manhattan’s Central Park. Instead, Jews established their own enclave on the west side of the Park, the neighborhoods called the Upper West Side and Morningside Heights. That was Harry Sophian’s working territory. The luxury apartment building blossomed in those neighborhoods. Immigrant architects (both Italian and Jewish) designed extravagant buildings that became home to the extraordinarily wealthy as well as the merely affluent.

There are a few architects and buildings that Harry might have found inspiration. Emery Roth, a Jewish architect of renown, designed many apartment buildings on the Upper West Side. His reputation bloomed after he designed the famous Chocolate Pavilion at the 1893 Columbian Exposition, the showcase event for the Beaux Art movement. Notice the colonnade, Corinthian columns, balustrade, and free-standing statuary of the pavilion. Each are central features of Beaux Art design, and each was incorporated into the Sophian Plaza design.

1893 Columbian Exposition

Showcase for beaux arts architectural design

Chocolate Pavilion, architect Emery Roth

The Upper West Side apartment houses were grand, heavily ornamented, and designed in various architectural styles, most notably Beaux-Arts. These new buildings offered apartments of nine to twelve rooms. The chambers were large, with high ceilings and lavish interior details, including well-appointed bathrooms and kitchens, and ample closets.

A promotional book featuring select apartment buildings was produced annually, Apartment Houses of the Metropolis. They were created to entice potential middle- and upper-class tenants to New York City’s “principal high-class apartment houses.” It provides a glimpse into the exuberance of apartment house building on the Upper West Side. These 300-page volumes showed exterior shots of the featured buildings with description and often one or more floor plans. They were published annually from 1908 to 1913. The excerpts below are from the 1908 edition.

From these few examples, one can see parallels to the Sophian Plaza design. Limestone clad lower floors, topped with brick upper floors. Commonly, the building’s footprint was crafted to allow multiple facades for windows and air circulation.

Two of Harry’s siblings lived in buildings that were featured in these promotional books, Abraham and Rosie.

The Orienta

302 West 79th street

Abraham and Estelle Sophian’s residence, 1915 (per his passport application)

The st regis

830 East 163rd Street, Bronx

Rosie [Sophian] and Morris Rabinowitz residence, 1910 (per the Census)

Kansas City historians have traced the development of apartment buildings here, noting that a segment of the upper-middle class emerged as an important subpopulation of apartment dwellers in the late 1880s forward. As the old elite neighborhoods close to the business centers declined, “apartment hotels offered amenities typically provided by hotels located on major thoroughfares with streetcar lines near the City's business centers. These new residential buildings featured an array of facilities and services for those without the time or inclination to manage a large home - kitchen, laundry, and maid services; well-appointed public rooms; and private suites that included parlors, dining rooms. bedrooms, bathrooms, and maid quarters. Social registers from the first decades of the twentieth century reveal that these apartments appealed to the upper-middle classes, including professionals, businessmen, and entrepreneurs.” Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Buildings in Kansas City, Missouri, National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form (Sept. 20, 2007).

The Sophian Plaza was conceived and designed to fit this role.

The Story of the Sophian Plaza starts with . . . Harry’s first Kansas City Apartment House

Harry Sophian, a Russian emigré at age nine, lived and worked as a “real estate man” in New York City, during a time when development of tall apartment buildings (8-12 stories) was exploding, especially along Manhattan’s upper west side. As a transplant to Kansas City, he imported a well-developed vision of elegant apartment living. He arrived in Kansas City in 1916, and set to build his first apartment house, the Georgian Court apartment hotel.

Armour Boulevard and

main street

He selected a site at the auspicious corner of Armour Boulevard and Gillham Road, two blocks from the mansion of Kirkland Armour, meat packing magnate, and other Kansas City luminaries. The KC History site (Midtown KC Post) describes just how fashionable Armour Boulevard was in this time. According to Midtown KC Post, at the turn of the 20th century, Armour Boulevard was one of the most celebrated streets in town, proudly featured in numerous postcards of the day showing off Kansas City’s new boulevard system.

Harry purchased the corner lot in 1917 (Jan 2), with architectural plans already in hand. He attracted the financing might of bankers from New York and Chicago to underwrite the building, and broke ground (Jan 11) to build an eight-story apartment hotel. With speed that is remarkable in today’s terms, he declared the building would be ready for occupancy as early as October 1917. Although Harry was the man-on-the-ground, the bond financing notice shows that the new building was jointly owned by Harry and Jane, Abraham and Estelle Sophian. Shepard, Farrar & Wiser were the architects. The Kansas City Star article announcing the building’s debut, noted that its “appointments will be elaborate beyond anything yet attempted here.” (KC Star, 1-17-1917).

Georgian Court opened in 1917

The building offered 24 large apartments, most were 9-rooms, “exceptionally large and light,” including large foyers, sun parlors, breakfast rooms, and sleeping porches. A pergola and ballroom were planned for the top floor. The announcement included details about provisions for service staff, which included day and night elevator service, hall service, and footmen, all of whom would be attired in uniforms, and for whom onsite dormitory accommodations would be provided.

Architectural historians, Ellen Uguccioni and Sherry Piland noted that Georgian Court Apartment Hotel started the high-rise building boom here. The Georgian Court was deluxe and “set a standard for the others that were to follow. It had no rivals.” (Armour Boulevard, National Register of Historic Places).

Armour Boulevard (1918)

Glimpses In And Around Kansas City

(Fred Harvey)

The building filled its 24 apartments quickly. In a marketing coup, I suspect Harry Sophian nudged the folks at Kellogg-Baxter, the publishers of the Social Register, to include every family who became a tenant in the 1918-19 Kansas City Social Register. Twenty-four apartments, twenty-four families on the Social Register listed their address at Georgian Court, 400 East Armour Boulevard.

“The Georgian Court was deluxe and “set a standard for the others that were to follow. It had no rivals.””

Developing the Georgian Court apartment hotel was a personal success for Harry Sophian. It was credited with transforming Armour Boulevard, and ushering in a new era of high-rise apartment living on the Boulevard, so much so that it is now its own historic district, Armour/Gillham Apartment Hotel Historic District (local district, designated May 27, 1982).

Harry was ready for the next project, The Sophian Plaza, on Warwick Boulevard, flanking Southmoreland Park. The site held an array of benefits.

First, it was very close to very wealthy people. William Rockhill Nelson’s baronial manse, Oak Hall, was on the opposing side of the park, and two blocks up Warwick Boulevard was August Meyer’s palatial home, Marburg. Nelson was the Kansas City Star publisher and a real estate developer. Meyer was a mining and smelting magnate. [Nearness to the wealthy families along Armour Boulevard had been critical to the Georgian Court’s fame.]

William Rockhill Nelson’s

Oak Hall

August Meyer’s

Marburg

Second, the site was reminiscent of the parks of New York City. Harry and his wife, Jane, brother Abe and his wife, Estelle, all spent their early adulthood years in New York, around Central Park, Morningside Heights Park, and Riverside Park—each was designed by venerated landscape architecture team of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Olmsted and Vaux designed parks to heighten the enjoyment and aesthetics of the turf, water, and rock of the landscape and its natural contours, using gentle, sprawling lawns, winding pathways, natural woodlands, and rock outcroppings. Southmoreland had that look and feel.

Third, Meyer and Nelson were intent to craft the Rockhill and Southmoreland neighborhoods with very specific design elements in mind. They were natural admirers of Olmsted and Vaux’s work, and approached building their neighborhood to fit with that aesthetic. Their vision for the neighborhood was an extension of the City Beautiful Movement--naturalistic landscaping, open parkland, native stone for fences, and curved roadways lined with elm trees.

Southmoreland Park is a natural ravine, through which a small brook runs in the rainy times. The cliffside of the ravine is protected by a limestone retaining wall. [We have yet to learn when the park was designed and embankment built.] The plot of land was first platted by W.B. Clark as South Moreland Addition. It was eventually acquired by Nelson, and given to the City for street and park purposes.

The City Accepts

gift of

South Moreland park

Kansas City Journal, October 21, 1898

Nelson turned his attention to the roadways through the neighborhood. He orchestrated the renaming of Grand Avenue and McGee Streets, to more bucolic names, Warwick Boulevard and Oak Street to flank Southmoreland Park (September 1898). Per Harry Haskell, in Boss-Busters and Sin Hounds: Kansas City and Its Star (2007), Nelson doted over and groomed Warwick Boulevard. He badgered the city of Westport to pave the dirt roadway; ultimately paid the asphalt company owned by the Police Commissioner to pave it; and made sure to plant rows of elm trees along the sweep of its borders.

Indeed when there had been an attempt to change the character of the neighborhood by widening Walnut Street, everyone “knew” it would not be tolerated by Nelson and Meyer. The proposal prompted the mayor to make a personal inspection of the area. And he summarily vetoed the proposal, declaring that a street widening would do vandalism to the area. “The addition of South Morelands is one of the few in Kansas City where streets have been laid out to suit the contour of the ground, and where an attempt has been made to preserve the park-like character of the property and remove from it the ordinary characteristics of city lots.” (KC Journal 7-19-1899).

Rockhill Boulevard

Circa 1920’s

Nelson’s Oak Hall in the Background

Nelson and Meyer’s design sensibilities drew admirers. Soon the neighborhood was dotted with mansions of some of the City’s most prosperous families. By 1919, when Harry purchased the lot for The Sophian Plaza, the immediate neighbors included Mrs. Simeon Armour, widow of the meatpacking tycoon; Stephen Veile, grandson of John Deere; Gardner Lathrop, one of the most widely known lawyers in Missouri; W. B. Thayer, owner of Emery, Bird & Thayer dry goods company, among other luminaries. [Link to section on the Homes of Note in the Southmoreland neighborhood, as of 1919]

In a neighborhood that evoked the venerated parks of New York City, and in the company of some of the wealthiest citizens of the City, Harry was ready to design and build the eponymous apartment house, Sophian Plaza. When he announced the building plans, specifically noted, “We will face Southmoreland Park and overlook Warwick Boulevard as it curves along the edge of that secluded park space. When I was fortunate enough to obtain this site a few years ago, I appreciated the suburban atmosphere.”

““We will face Southmoreland Park and overlook Warwick Boulevard as it curves along the edge of that secluded park space.” ”

As “perfect” as the site was for Harry’s vision for his next building project, he also faced headwinds in building a new apartment hotel. Nelson’s Rockhill development to the east of Oak Hall and JC Nichol’s Country Club developments south of Brush Creek were known for their exclusionary sales and rentals practices against Black and Jewish people.

JC Nichols was well known for developing deed restrictions that were ironclad and stood the test of time. Many of the restrictions pertained to issues like allowable materials to be used in the home construction, setbacks, and the like. The ones that were most venal were the restrictions of who could purchase or rent in these neighborhoods. A typical restriction read: “No lot shall be conveyed to, used, owned, nor occupied by negroes as owners or tenants.” Jews were not expressly included within restrictions, but they were patently included by practice.

“restricted”

“protected”

JC Nichols was a member of a national league of developers (called the “High Class Developers Conference”) which kept detailed records of their meetings. William S. Worley in his highly regarded book, JC Nichols and the Shaping of Kansas City (1990), recounts that the members worried about selling to “Jews and Orientals.” In their 1917 meeting, Nichols explained that his policy was not to sell to Jews, but acknowledged that four or five Jewish families have houses on his properties through other sellers. He noted that he was getting pressure from Jewish leaders to open sales to Jewish families. Other developers urged him to resist, noted that his resistance would be good for sales, and offered stories of their “fortitude” to cancel contracts summarily when they learned the purchasers were Jewish.

This was the world that Harry Sophian faced as a Jewish developer and that Jewish families faced when looking for hospitable places to live. When Harry Sophian finally purchased this plot of land between Rockhill and Country Club districts, he made an announcement referring to his unwelcoming neighbors and proudly claiming that his building would be enviable.

He specifically noted the “restricted home areas” that surround his Warwick Boulevard site, and extolled the amenities, aesthetics, and virtues of the planned new building. With real estate bravado, he noted that he directed his architects to design “a structure that will measure up to its environment out there on the edge of the Rockhill district. … I told my architects to instill into towering brick and stone the fine residential character of the neighborhood.” The architects were told “there would be no skimping in carrying out a pure Italian design.”

“Harry Sophian’s answer to the racist anti-semitic developers:

My architects will design “a structure that will measure up to its environment out there on the edge of the Rockhill district, and .... instill into towering brick and stone the fine residential character of the neighborhood.””

On June 7, 1919, Harry Sophian purchased a triangle of land, on Warwick Boulevard, between 46th and 47th Streets, from Henry Schott, a marketing vice president at Montgomery Ward catalogue company and former editor of the Kansas City Star.

With the announcement of the land purchase, Harry previewed his plans—a 10-story apartment building with 30 apartments of 8- to 12-rooms, each with servant quarters within the apartment. A building notably grander than the Georgian Court. Indeed, Harry raised $180,000 to build the Georgian Court apartment house. And he announced that the Sophian Plaza will be a $1,000,000 building.

According the KC Star news account (6/8/1919), Wight & Wight architecture firm was engaged to create a building of Italian Renaissance design, with every room to have windows. At the time Harry hoped for occupancy in 1920.

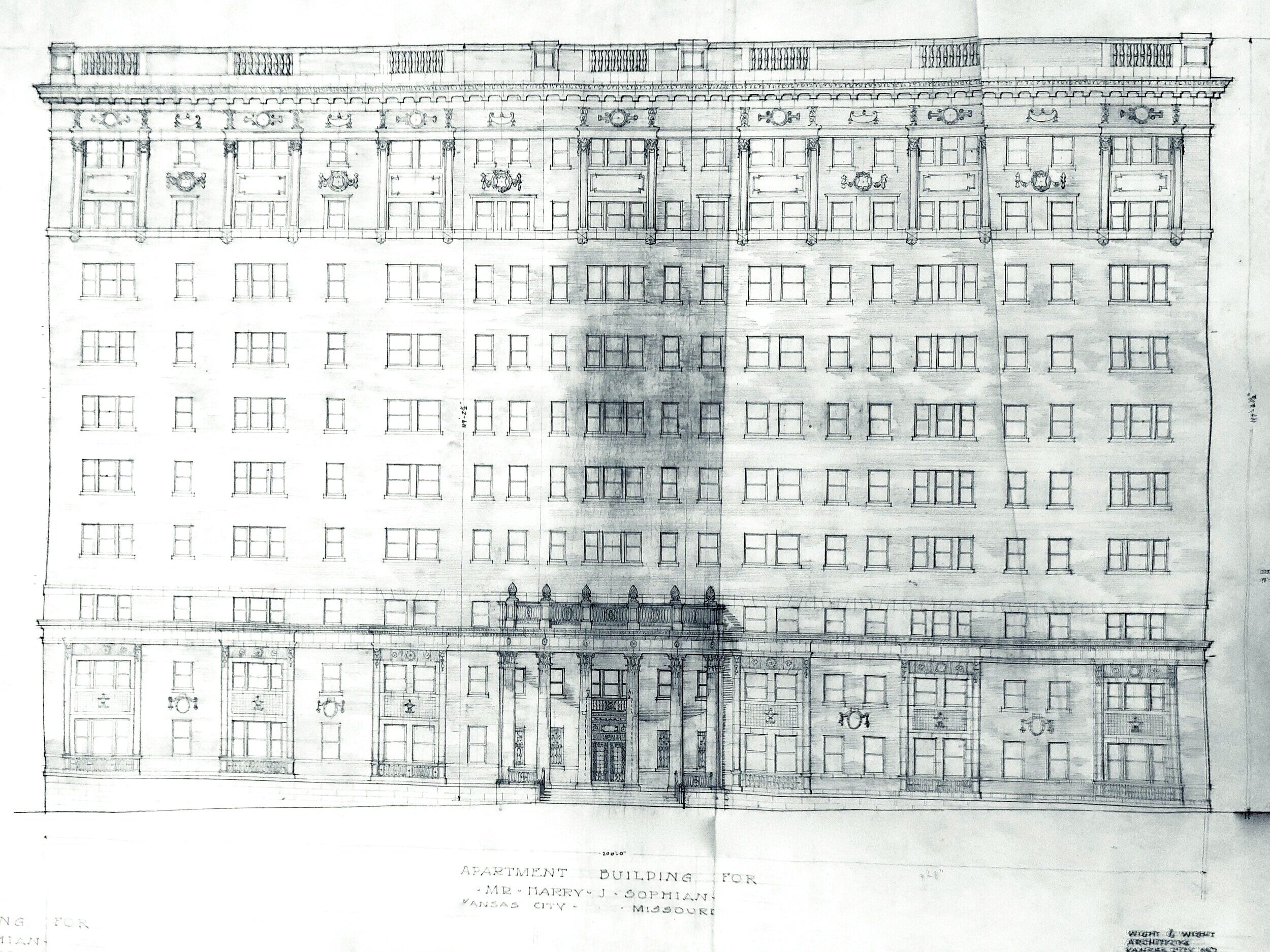

We found the Wight & Wight architectural plans at the State Historic Preservation Office. They developed a Beaux Arts design for a three-spoked building. But they were never advanced. Instead, Sophian switched design firms, returning to Charles Shepard, of Shepard & Wiser.

Renderings of Sophian Plaza, elevations and plan, undated, circa 1919, by Architects Wight and Wight; Engineer Tuttle Ayers Woodward, Box 137.019, Wight and Wight Architectural Records, 1904-1952 (K0825); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center Kansas City.

We have yet to discover the reason for changing architectural firms. But a few things are apparent about Sophian’s connection to Charles Shepard, that may have precipitated the engagement. Charles was a familiar figure. Harry had already worked with Shepard, who designed Georgian Court. Shepard, his wife Anna, and their two sons, Theodore and C. Edwin, lived in Georgian Court and were likely next door neighbors (on the same floor) with Harry, Jane and Lucille. The 1920 census records show the Shepard family entries immediately preceding the Harry Sophian family notations. And it turned out that JC Nichols, the outsized developer of Country Club district, had just purchased a Charles Shepard designed home. Shepard’s reputation was growing brightly. (See more details on the JC Nichols home, at Shepard & Wiser, Architectural Firm of High Repute, below).

With second round of fanfare, Sophian’s new plan was revealed, including Shepard’s renderings, maps, and an extended article in the Kansas City Star, April 9, 1922.

Showing the Street plan at the time the building was planned

Kansas City Star, April 9, 1922

In several way, Shepard & Wiser’s subsequent plan shows a consistency of Harry Sophian’s vision. Colossal columns, topped with Corinthian capitals. An elaborate architrave with a balustrade railing. Free-standing statuary. These were the elements that Harry saw as indicative of Italian Renaissance style. In other ways, the Shepard & Wiser plan was more modest than first projected. Nine stories, not ten. Apartments with 4- to 7-rooms, smaller than the 8- to 12-room apartments originally projected. Sophian explained, it represented a larger investment, $1 million, of pure Italian architecture, which was intended to present an even more imposing appearance.

Shepard & Wiser design

East (Front) Elevation

May 29, 1922 plans (not final)

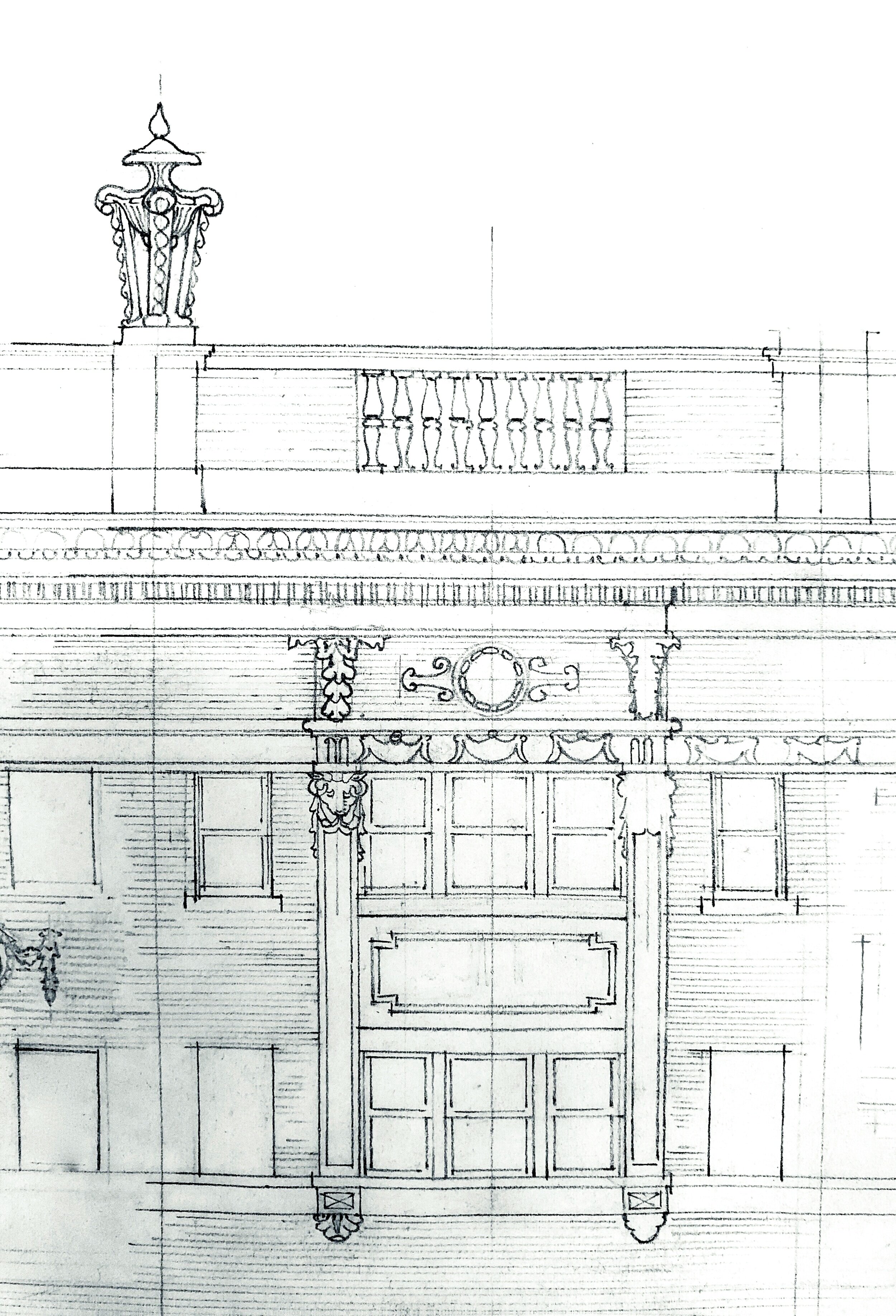

Shepard & Wiser

Front Courtyard detail

The reduced profile of the building may well have been a cautious reaction to the fevered pitch of apartment construction in Kansas City at the time. In the years from 1920 to 1922, apartment building “starts” grew from buildings that totaled 382 units valued about $ ¾ million in 1920 to buildings with 1,620 units, valued at nearly $9 million, by 1922. (Kansas City Working-Class and Middle-Income Apartment Building History, National Register of Historic Places, 9-20-2007). Additionally, it appears that he raised $429,000, through issuing 30 year, 5% bonds, not the million dollars he first trumpeted. [In a later post, we will describe the financing and sales of the building over the years. Business records available in the Missouri State Historic archives provide much detail.]

The Manhattan Construction Company was engaged to handle the construction. The foundation permit was taken out in April 1922. The Manhattan Construction Company was founded in 1896, in Oklahoma. It was (and still is) family-owned. Today (2020), it touts itself as among the largest family-owned construction companies in the US. The company provides pre-construction, construction management, program management, general building, and design-build services throughout the United States, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean.

As the Sophian Plaza construction progressed, Kansas City Star regularly reported developments regarding the building, with renderings, photos, and news updates.

And on February 25, 1923, the Kansas City Star trumpeted the opening with the headline, “The Sophian Plaza, A New Million Dollar Apartment Building Is an Imposing Structure of Italian Architecture.” According to the Star report, the Sophian Plaza “stands as a structure of high character.”

Below we show the renderings of Wight & Wight, the first architects hired by Harry Sophian for the Sophian Plaza.

When he announced his plans, covered by the Kansas City Star, June 8, 1919, he described a building of 10 stories, with just three apartments per floor. Wight & Wight’s renderings were not presented at that time. Sophian noted to the Star reporters that he did not expect the construction to start until Fall 1920, a year away. The drawings shown below are undated, but I am presuming around 1919, early 1920 to prepare for bidding documents to hire a contractor. These plans were located State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center- Kansas City.

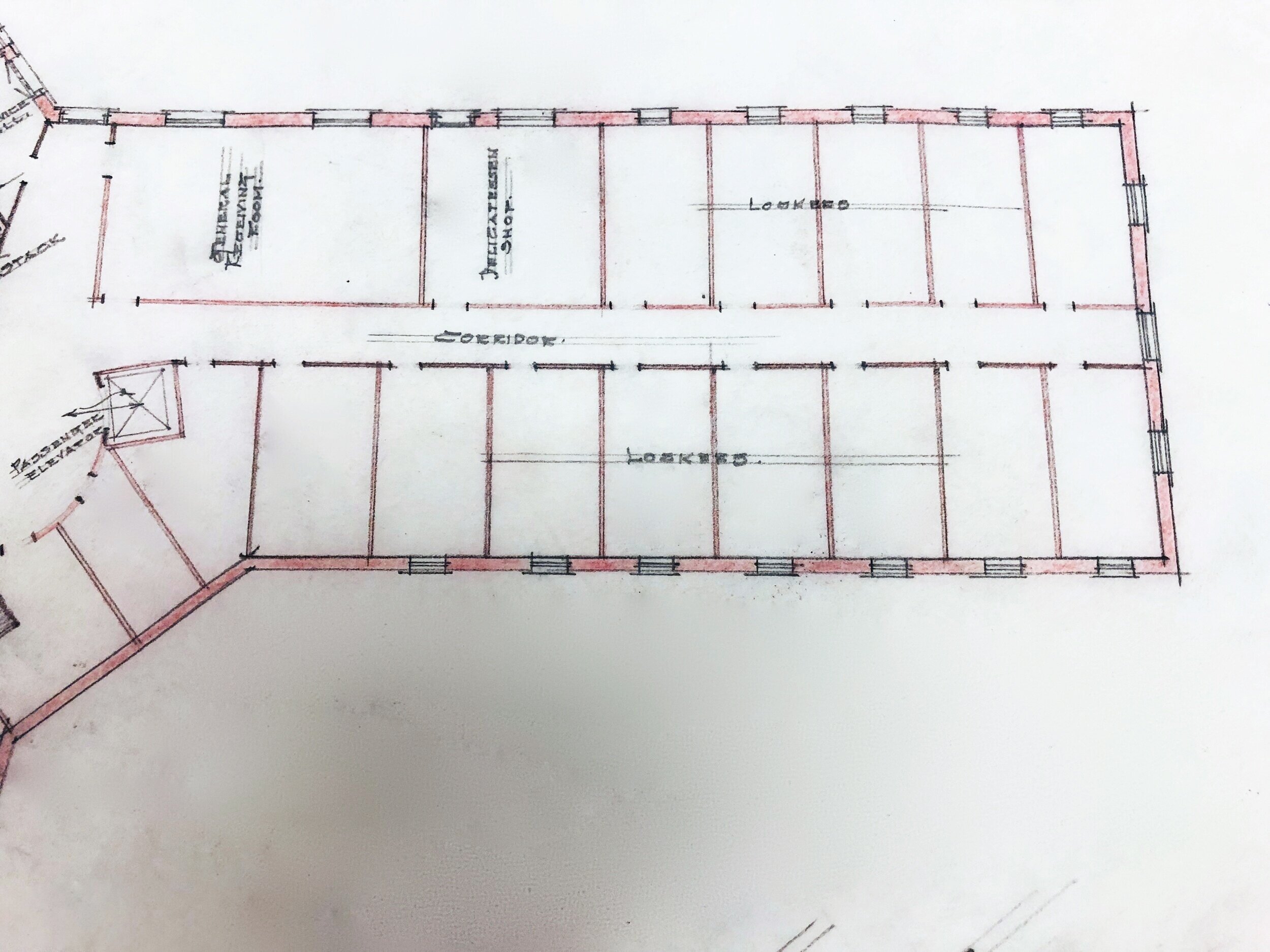

The pinwheel design of the building allowed for one apartment per wing, with plenty of windows on both sides of each apartment, for optimal air circulation. The building would provide accommodations within the apartments for live-in household staff, as well as accommodations on the ground floor for “maids’ rooms” and many lockers, for the day workers. The garage for residents would be accessed from Brush Creek Parkway (present-day, Emanuel Cleaver II Boulevard).

Wight & Wight were his designers. were architects of high reputation. They designed the Nelson Atkins Museum, among other sites. The firm was known for its Neo-Classical design style, exceptional command of mass and proportion, and exquisite attention to details. Thomas (1874-1949) and William Drewin (1882-1947) Wight were brothers, born in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Thomas worked for the venerable firm, McKim, Mead, and White, as a draftsman and then architect, agreeing to an employment term of ten years before starting his own firm. Brother, William, traveled the same path, working with McKim, Mead, and White for ten years and then joining his brother in Kansas City.

“J Sophian, Proposed Apartment,” (circa 1919) Wight and Wight Architectural Records, 1904-1952, Box K 0825, The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center- Kansas City.

Full view of East elevation, entrance on Warwick Boulevard.

Detail of the roof line and ornamentation of upper floor windows.

East elevation, front entrance, Warwick Boulevard

First floor plan, showing rotunda lobby, and apartment layouts on each wing. Apartments had three to four bedrooms for the family, each with private bathroom, plus living room, dining room, sun room, and den. There were also small suites for the live-in household staff, behind the kitchen.

Ground floor plan. Details of each wing below.

Ground floor plan, South wing (Maid’s accommodations, resident oriented businesses, e.g., tailor, barber, hair and nail salon).

Ground floor plan, West wing. (Kitchen, bakery, pantry, cool room, dishwashing, receiving)

Ground floor plan, North wing (Lockers, receiving, delicatessen)

Charles E. Shepard, architect for the Sophian Plaza, was an active and highly regarded architect in Kansas City. He had multiple partnerships over his forty-five-year career from 1887 to 1931, including with Albert Wiser and Ernest Farrar. Sometimes organized as Shepard & Wiser, or Shepard & Farrar, or Shepard, Farrar & Wiser. According to Michael John Ray, architect and appraiser of Kansas City’s historic architecture, Shepard was the “Shepard was the principal designer of every building type found not only in Kansas City, but also in Tulsa, Wichita, and Amarillo, Texas. In the metropolitan area it is documented that Shepard left a rich tradition of architecture, including the design of over 600 residences located in Hyde Park, Mission Hills and the Country Club District.”

Ray was so enchanted with Shepard’s work that he spent two sunny days drawing the building in beautiful oxblood colored pencil. He posted multiples of the Sophian Plaza. (March 23 and 26, 2010), titled Best Addresses, on his blog, Analytique.

Many of Shepard’s buildings have stood the test of time (still exist and in productive use today) and the test of design. Numerous buildings have been named to the Register of Historic Places. Nota bene: Another architect, active in the same time period in Kansas City, was Clarence Erasmus Shepard. There are many references to CE Shepard that are for Clarence, not Charles).

Part of Charles Shepard’s allure to Harry Sophian no doubt was the acclaim he reaped from his design for the grand home of Charles Keith, a lumber baron, located in the highly restricted Sunset Hill Subdivision in the famed Country Club District (Ward Parkway at one of the most important intersections, 55th Street). Importantly, the rock star developer, JC Nichols bought the home from Keith in 1920, just as Harry was terminating his engagement the first architecture firm, Wight & Wight, and switching to Shepard & Wiser.

Charles Keith House (1913)

photo courtesy of State Historical Society of Missouri

The Keith/Nichols house has twenty-two rooms, plus six full bathrooms. Exterior features included the use of elaborate cut-stone trim work, multiple pergolas, and a large carriage house. The three-acre grounds were designed by Kansas City landscape architecture firm Hare and Hare. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places February 18, 2000.

The President Hotel (1926)

Detail of top floors

Shortly after completing the Sophian Plaza, Shepard was commissioned to design The President Hotel, in downtown Kansas City. The hotel was built in 1924-26, during a construction boom (that also saw the erection of the nearby Mainstreet Theater, Midland Theatre, and Kansas City Power and Light Building.

It was one of KC’s grand hotels, with 453 guest rooms, and the distinction of being the first hotel to make ice on premise. The hotel served as the site for the 1928 Republican National Convention, which nominated Herbert Hoover for President. The hotel's Drum Room lounge attracted entertainers from across the country, including Frank Sinatra, Benny Goodman, and Marilyn Maye.

The hotel underwent a $45.4 million restoration project meeting the exacting specifications of the National Historic Preservation Society in many areas of the hotel. To meet the modern standards of luxury accommodations, guestrooms were enlarged to offer a total of 213 guest rooms and suites. In keeping with preservation requirements, and to maintain the look of the original hallways, there are eight faux doors on each floor. In January 2006, the hotel reopened as Hilton President Kansas City and has since maintained its celebrated heritage without sacrificing modern conveniences. The Hotel President was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 8, 1983.

The Deramus Building (1925)

The building at 301 West 11th Street, was designed by Shepard &. Wiser, for the W.R. Pickering Lumber Company at a cost of approximately $400,000. The Second Renaissance Revival Style building has several additions constructed in the 1950’s and 1960’s, which were designed to complement the historic building and are considered to be an integral part of the building’ s overall design. The building is now commercial office space, known as the Deramus Building. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.

The building has since undergone a substantial façade rehabilitation, with the historic preservation consultation of Strata Architects. The image is from the Strata Architects website.