As “perfect” as the site was for Harry’s vision for his next building project, he also faced headwinds in building a new apartment hotel. Nelson’s Rockhill development to the east of Oak Hall and JC Nichol’s Country Club developments south of Brush Creek were known for their exclusionary sales and rentals practices against Black and Jewish people.

JC Nichols was well known for developing deed restrictions that were ironclad and stood the test of time. Many of the restrictions pertained to issues like allowable materials to be used in the home construction, setbacks, and the like. The ones that were most venal were the restrictions of who could purchase or rent in these neighborhoods. A typical restriction read: “No lot shall be conveyed to, used, owned, nor occupied by negroes as owners or tenants.” Jews were not expressly included within restrictions, but they were patently included by practice.

“restricted”

“protected”

JC Nichols was a member of a national league of developers (called the “High Class Developers Conference”) which kept detailed records of their meetings. William S. Worley in his highly regarded book, JC Nichols and the Shaping of Kansas City (1990), recounts that the members worried about selling to “Jews and Orientals.” In their 1917 meeting, Nichols explained that his policy was not to sell to Jews, but acknowledged that four or five Jewish families have houses on his properties through other sellers. He noted that he was getting pressure from Jewish leaders to open sales to Jewish families. Other developers urged him to resist, noted that his resistance would be good for sales, and offered stories of their “fortitude” to cancel contracts summarily when they learned the purchasers were Jewish.

This was the world that Harry Sophian faced as a Jewish developer and that Jewish families faced when looking for hospitable places to live. When Harry Sophian finally purchased this plot of land between Rockhill and Country Club districts, he made an announcement referring to his unwelcoming neighbors and proudly claiming that his building would be enviable.

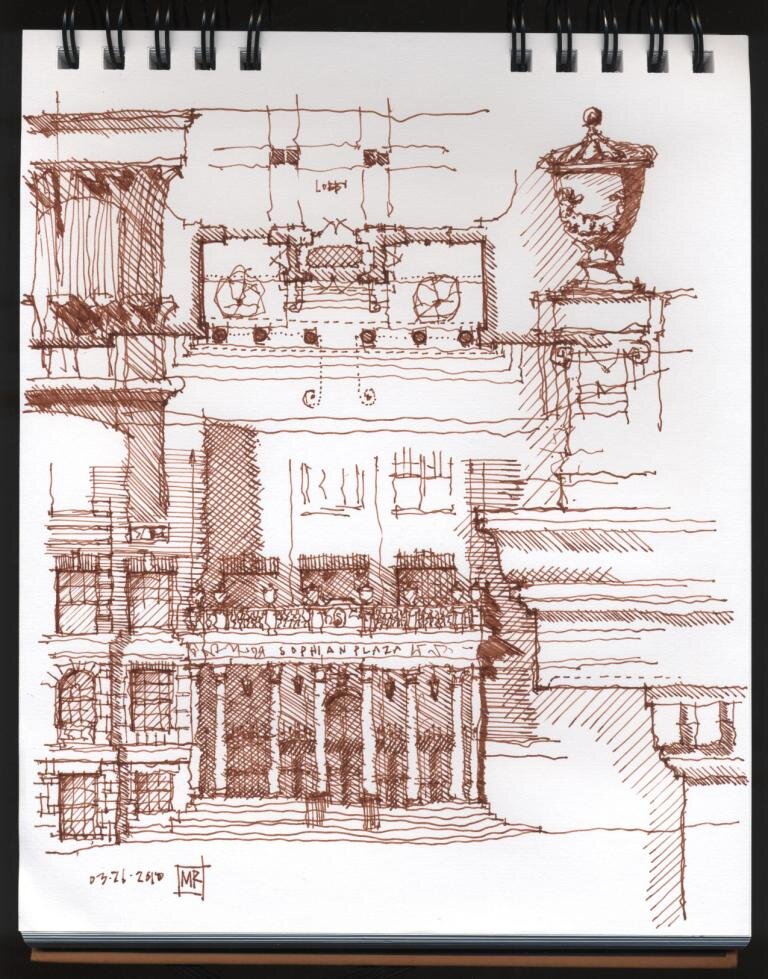

He specifically noted the “restricted home areas” that surround his Warwick Boulevard site, and extolled the amenities, aesthetics, and virtues of the planned new building. With real estate bravado, he noted that he directed his architects to design “a structure that will measure up to its environment out there on the edge of the Rockhill district. … I told my architects to instill into towering brick and stone the fine residential character of the neighborhood.” The architects were told “there would be no skimping in carrying out a pure Italian design.”

“Harry Sophian’s answer to the racist anti-semitic developers:

My architects will design “a structure that will measure up to its environment out there on the edge of the Rockhill district, and .... instill into towering brick and stone the fine residential character of the neighborhood.””